Dress in the Age of Jane Austen has been a long time coming. It started out as a chance comment in 2013 from Professor Aileen Ribeiro, author of foundational books on dress history such as The Art of Dress: Fashion in England and France 1750 to 1820. We were standing chatting in the snowy grounds of Chawton House, once owned by Jane Austen’s brother Edward Knight, who was adopted by childless cousins and changed his surname. The gracious Elizabethan manor had become a center for studying women’s lives and writings, but we were there for the filming of the BBC documentary Pride and Prejudice: Having a Ball, which sought to recreate the famous Netherfield ball scene from Jane Austen’s most beloved novel. I had made a hand-stitched replica gown for the production and appeared as the costume expert. During conversation, Professor Ribeiro mused on the fact that there was no good book on Regency dress. I agreed, but was taken by (flattered) surprise when she said she thought I would be the perfect person to write one. The conversation moved on. However, the idea’s seed started growing quietly in the back of my head. Six months later, I had decided to write what I privately thought of as The Big Book of Regency Dress.

My introduction to the clothes of Britain’s Regency period (c. 1795-1821) was through the body and life of Jane Austen, by recreating a silk pelisse coat, the only known garment connected with the author. Her incredibly observant writing, combined with the breadth of research existing on her and her family, made Austen the perfect starting point. Because I began with her physicality, I mused on the importance of the bodily self as the starting point for imagining and wearing fashion. From this center emerged the book’s structure, which moves outwards in concentric circles from Self, through the experiences of Home, Village, Country, City, Nation and finally, World. Locating seemingly English local fashions within their wider global contexts was important to me as an Australian historian. Without Britain’s world trade, none of the heaving bosoms dear to screen adaptations would have been clad in muslin gowns and Kashmir shawls.

My introduction to the clothes of Britain’s Regency period (c. 1795-1821) was through the body and life of Jane Austen, by recreating a silk pelisse coat, the only known garment connected with the author. Her incredibly observant writing, combined with the breadth of research existing on her and her family, made Austen the perfect starting point. Because I began with her physicality, I mused on the importance of the bodily self as the starting point for imagining and wearing fashion. From this center emerged the book’s structure, which moves outwards in concentric circles from Self, through the experiences of Home, Village, Country, City, Nation and finally, World. Locating seemingly English local fashions within their wider global contexts was important to me as an Australian historian. Without Britain’s world trade, none of the heaving bosoms dear to screen adaptations would have been clad in muslin gowns and Kashmir shawls.

I also wanted to go back to first principles. Regency fashion attracts a lot of myths, like that women stopped wearing stays or corsets, or damped their dresses to achieve a clinging fit. Did they really? And if not, what were Austen’s gentry peers actually wearing? The research involved scouring every kind of source I could think of, peering into people’s washing lists, their account books and recipes, taking advice from professionals of the time, and reading a lot of second-rate fiction. I also amassed thousands of images of clothed Regency people, only a comparative few of which appear in the book. Here’s some that didn’t make it.

Continuing an 18th-century tradition of depicting scholarly men in loose “banyans” or robes, this “virtuoso” of 1796 combines the domestic informality or undress of a turban and plaid gown—probably made of Indian Madras checked cotton—with outdoor shoes with buckles. The corner of his by now old-fashioned waistcoat with long skirts peeps from below his gown.

Anglo-Irish author Maria Edgeworth’s letters are a font of information about dress and dressing practices. By comparison, only 161 of an estimated 3,000 of Austen’s letters survive. Edgeworth moved in more exalted social circles as a celebrated author, which Austen unfortunately never lived to experience. The Edgeworth letters share fashion details of the aristocracy as well as her tactics for dressing well in such company. In this portrait, the writer wears a blue satin gown, and her age-appropriate cap is bedecked with matching ribbons.

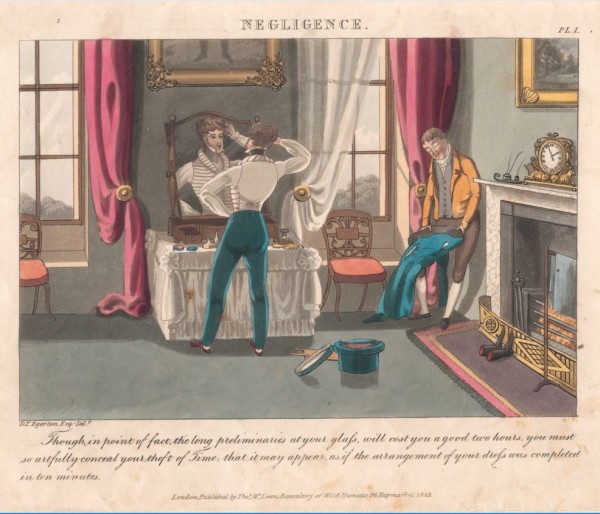

Images of dressing practices are harder to find than the finished ensembles. In a satirical yet detailed portrayal of the effort required to appear negligibly dressed, as was the fashion, many intimate aspects of the male dressing room are revealed. The snoozing servant’s clothing, including knee breeches, is less up to date than his master who wears newly fashionable trousers.

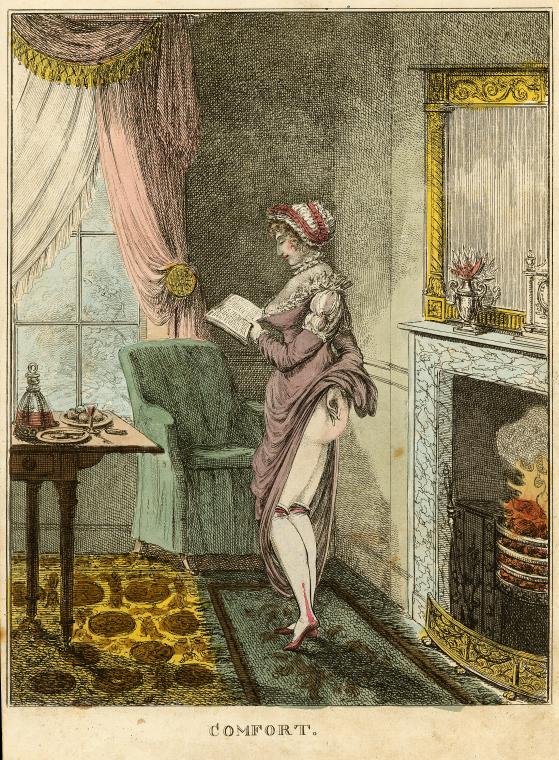

Regency women didn’t wear underpants. She is reading a copy of The Monk by Matthew Lewis, a wildly popular Gothic novel of the sort Jane Austen sends up in Northanger Abbey.

Englishwomen wore bright red worsted or woolen cloaks throughout the 18th century and into the Regency period. Foreign visitors thought them a peculiar and charming local style. Visual sources show the ubiquitous scarlet garments worn in the country by everyone from local gentry girls through to peddlers and street sellers.

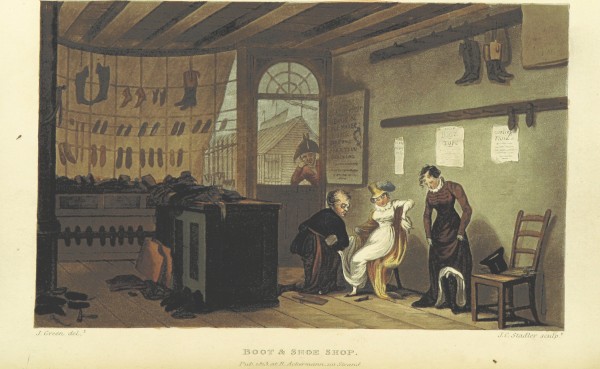

A vision of unpretentious provincial retailing of footwear in the popular seaside resort of Scarborough. The lady in a white cotton gown and voluminous cloak is being fitted for a pair of the heelless shoes that entered fashion around 1800. Her companion wears a woolen riding habit, worn on horseback and for travel. Habits took their cues from men’s fashion, further reflected in her Hessian boots and top hat.

Thomas Lawrence’s luminous depiction of an unknown sitter glows with life, satin, and nipples. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the engineering of Regency breasts, and how women used changing shapes in corsetry to support their busts—the key part of the new high-waisted silhouette. The brooch in the center front, and the gathers falling from it, show there is still a structured undergarment below this seemingly draped gown.

French and English fashions mutually borrowed from each other during the Regency period, as the title of this print from the series Le Bon Genre suggests. The subtleties of difference in each nation’s fashions are harder to reconstruct from the distance of a couple of centuries. To contemporary viewers the distinctions were clear. It would have been evident without the title that here were French girls dressed in English fashions, and vice versa.

Riding clothing was one of the strongest dress influences for the Regency gentry. Knee-high boots, cut away coats, and caped great coats imitating coachmen’s weatherproof garments suffused gentlemen’s dress. The peaked cap worn by jockeys such as Frank Buckle was fashionable for women, too. In 1811 Jane Austen wrote that “now nothing can satisfy me but I must have a straw hat, of the riding-hat shape, like Mrs. Tilson’s; & a young woman in this Neighbourhood is actually making me one.” It would cost her a guinea (a pound and a shilling).

The arts of making dress were of far greater importance to Regency people than they are today. Clothes were nearly all custom made, usually by dressmakers and tailors, and the gentry understood the construction processes. This comical figure is a tailor comprised from the tools of his trade. The artifacts of making would have been familiar to every man who had fittings in the professional premises, or at home. Even villages had at least a tailor or two. A quality garment was judged through the hands as much as the eye, and style could not be achieved without good fit.

The world of British Regency dress, seen through the lens of Jane Austen’s life and work, has been my constant companion in the years since that wintery afternoon deep in Austen heartland. I’m delighted to be able to share the fruits of my labors, and give readers an insight into how she and her contemporaries wore, used, made and understood clothing, that fundamental part of all human culture.

This post was produced in partnership with Publishers Weekly.